Sometimes the largest and most intractable problems are best addressed with fewer words, rather than more. This is the central aim of our latest blog post on the topic of U.S.-Russian relations: ‘Ukraine’s Place in the U.S-Russia Relationship’.

At a time when the risks of strategic miscalculation between the world’s two greatest military powers are higher than at any time since the early 1980s, the author advocates boiling the U.S.-Russian relationship down to its bare essentials with the aim of defusing the current confrontation over Ukraine and moving both countries toward a new strategic understanding.

That the United States and Russia could fight an undisguised proxy war in Eastern Europe is unthinkable. Such an outcome would drive world affairs deeper into crisis and ruin the livelihoods of millions of Ukrainian and Russian citizens. The task at hand is to avoid military conflict in Ukraine and establish a new strategic framework between the two powers that will make future conflict less likely.

The key to this outcome is the recognition by all parties – Ukrainians included – that Ukraine’s natural role in international affairs is to serve as a neutral buffer state between Russia and the West.

Ukraine must not become part of NATO. Likewise, Ukraine must never be re-integrated into Russia by either military force or the use of underhanded ‘political technologies’. The Ukrainian people must retain a high level of self-determination and control over their affairs, but a line must be drawn that establishes without doubt or equivocation that Ukraine’s freedom is best served by its remaining outside the NATO alliance.

A QUESTION OF ENDGAMES

Western hawks will regard any promise made to Russia by President Biden that freezes Ukraine out of future NATO membership as a shameful capitulation and strategic defeat – a calamity with echoes of 1938 in the face of Russian saber-rattling. Russian President Putin would certainly claim a strategic and diplomatic victory, one that will likely embolden him to act aggressively in other arenas, including cyber-warfare, in the future.

But before we characterize Western accommodation on Ukraine’s NATO membership as out-and-out defeat, we should first ask ourselves what victory would look like. Are we entirely clear in our own minds regarding long-term goals? What is the endgame we envision for Ukraine? For Eastern Europe and the Caucasus? And for Russia itself?

When framing the Ukraine Question in our minds, we must first ask ourselves: Is the endgame we desire a belligerent Russia surrounded on its western and southern flanks by NATO satellites? Is our goal to push Russia into an ever-deeper strategic alliance with China? Have we given up the dream of a democratic Russia as an ally of the West?

THE RUSSIA-CHINA ALLIANCE

Some will contend that Russia and China have already formed a close partnership against the United States, and any moves to forestall their alliance should have taken place ten years ago. Others will argue that the vision of a democratic Russia that arose in 1991 was always a pipe dream doomed to defeat and disillusionment. Better to consign it to the ‘Dust Bin of History’ – like communism before it – they might argue.

To these arguments, we can only reply, first, that no alliance was ever formed that has continued in perpetuity, particularly one made between treacherous actors practiced at deceit — especially when those actors share a long border. The Russia-China Alliance will break down eventually, most likely sooner rather than later.

Those of us who were children during the Cold War remember the old alliance between China and the Soviet Union. That partnership was also characterized by many fine words and promises of eternal friendship, but characterized by paranoia and double-dealing. It was less than 20 years old before Chinese and Russian troops were exchanging fire along their Siberian border. So much for eternal friendship!

WAITING FOR THE NEXT GORBACHEV

Second, on the topic of Russian democracy, it is worth remembering that the finest minds in the U.S. could not conceive of men the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin until they had met them in the flesh. The received wisdom of the early 1980s was that the Soviet system could not produce men with an ounce of decency or a longing for Western freedoms. But the finest minds, it turns out, were wrong.

Why then, should we give up on the dream of a decent Russia if the finest minds today believe that Vladimir Putin has ruined all hope of a democratic future for his countrymen? If Stalin could not do so, then how is it possible that Putin has returned Russia to the 1500s, metaphorically speaking?

A better future for Russia and its satellite nations is possible, but achieving such an endgame will be all the harder if the West remains engaged in an ongoing geopolitical exercise to encircle Russia with NATO members and other U.S. military allies.

That we should defend the interests of other democratic nations and aspiring democracies goes without saying. It is a question of the means and tactics we deploy, set against the endgames that we envision and choose to pursue over the longer-term. Tactics that feed into Russian paranoia and bolster the support of Russian hard-liners will not increase the chances of the best possible outcome we desire.

Does this mean we should agree to all of Putin’s terms and cave into his pressure in full? Of course not. The West is going to have to play tough with Putin and his cronies for another decade, at a minimum. But this may mean tolerating certain outcomes that he can claim as tactical victories if these outcomes can be made to serve longer-term U.S. interests.

THE ROLE OF UKRAINE IN HISTORY

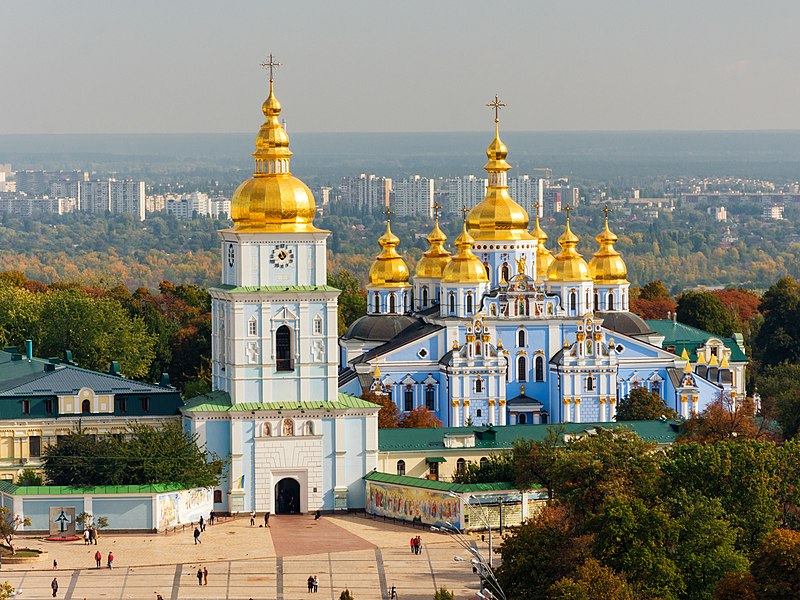

Ukraine is not a natural member of the Western military or diplomatic alliance. Ukraine’s history, culture, spoken languages and emotional affinities link it far more strongly to Russia and the broader sphere of Eastern Orthodoxy than to the West.

Historically, Ukraine has acted as a borderland between Russia and Central Europe, generally aligned with Russia but not always under Moscow’s direct control. Ukraine is the second largest nation in Europe after Russia as measured in square miles. At 45 million souls, Ukraine’s population is one-third that of Russia’s and greater than that of any other country in Eastern Europe. It is an agricultural breadbasket and industrial power.

Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire for most of the past 300 years. Prior to that, its trade and cultural links with Muscovy go back 1000 years. Between 1917 and 1991, Ukraine was a member state of the Soviet Union. Its people fought on the Soviet side of World War II against Germany and its allies, sustaining horrific casualties. Several of the largest land battles of WW II’s Eastern Front were fought within its borders. For these reasons, Russians and Ukrainians share deep emotional bonds.

Yet Ukraine is not a part of Russia proper and its people have lived through periods of terrible unpleasantness vis-a-vis the Kremlin. The Cossacks once resided in Ukraine in great numbers, and the drama of Cossack History – both as allies and as victims of Moscow – was played out on Ukrainian soil. An engineered famine in the 1930s, called Holodomor by Ukrainians, is another bitter memory given an estimated 5 million deaths from 1932-34.

In summation, then, it is safe to say that Ukraine’s ties to Moscow are deeper than its ties with the West, but Ukrainians nevertheless desire a level of autonomy from Russia given the unhappy experiences of its past, and particularly the traumas of the 20th century. Therefore, Ukraine’s natural role appears to be as a buffer between Russia and Western Europe.

Prior to the current crisis, it was desirable that Ukraine and its neighbors formally recognize Ukraine’s role as a neutral buffer state, controlled by no major power and bound to its neighbors by treaties of friendship and non-aggression. The present stand-off between Russia and the West provides an opportunity to make this condition official.

NATO’S WEAKER HAND

The United States retains the world’s largest military inclusive of all elements of its armed services. Moreover, our soldiers, sailors and pilots are battle-tested following a generation of engagements in Afghanistan and the Levant against the Taliban, ISIS and other adversaries.

The forces of our NATO allies and our combat troop strength in Europe, however, are but shadows of their Cold War might. Years of repeated troop draw-downs and spending of the ‘peace dividend’ on bank bailouts and generous social benefits have left the militaries of France, Germany, and other NATO members underfunded and poorly armored.

Take Germany as an example. Late in the Cold War, pre-reunification West Germany could field 1,500 fully operational tanks against an invasion from the east. When combined with similarly-sized French and American forces and the presumed support of British and Italian tank brigades, NATO was in a position to activate some 5,000 tanks to repulse a Warsaw Pact incursion.

Today, the reunified Germany is estimated to have less than 100 operational tanks split into four armored battalions – less than 5% of 1988 numbers. Backing up German armor are French and Italian tank brigades that sport armor in the low hundreds (150 – 300 tanks). At best, NATO heavy armor in Europe is at 10% to 15% of its late Cold War levels.

Match these numbers against the firepower of the rebuilt Russian land forces and one begins to see the dimensions of a problem. Russian land forces are organized into 168 battalion tactical groups (BTGs), each made up of roughly 850 soldiers and 40 tanks. Western military analysts have identified units from 100 BTGs in position around Ukraine’s defensive perimeter as of February 10.

If we assume that tanks in all 100 units are fully operational, then Vladimir Putin has roughly 4,000 tanks at his disposal. Doing the most rudimentary math, we must conclude that approximately two-thirds of Russia’s heavy armor is encircling Ukraine and is poised to strike.

In addition to tanks, the Russian military has increased its purchases of land based missiles, armored vehicles and heavy artillery. Russian military service members number around 1 million. On the Ukrainian border, an estimated 120,000 Russian troops confront a Ukrainian army numbered 260,000 strong dug into deep defensive positions but lacking the full range of tactical equipment and air power of their Russian counterparts.

NO DOMESTIC CONSENSUS

More worrisome than the armor and firepower imbalance between Russia and Ukraine and between European NATO forces and Russia in Europe is the level of internal division in the United States. Not since the Civil War have domestic U.S. political tensions been at such a fever pitch – a factor boosting Russia’s confidence that their pressure campaign will yield a favorable outcome for them. It’s not 1962 in America.

There is no consensus among American political leaders as to what role Ukraine should play in U.S. strategic considerations. A group of right-wing media personalities openly sides with Russia. Hawks on the left and right, by contrast, appear committed to admitting Ukraine into NATO at some future date. Centrists and doves are subdued.

Meanwhile, Democrats and Republicans are locked in a kind of ‘Cold Civil War’. Open hostility among members of Congress and a heavily radicalized Republican voter base (and radicalizing Democratic operatives) make near term consensus on major issues unlikely.

Passage of the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA) in November 2021 might represent the first green shoots of a return to more bipartisan lawmaking, but the tea leaves are extraordinarily hard to read while Donald Trump remains a political force.

Given the lack of public support for U.S. actions that go beyond selling arms to the Ukrainians and shifting around troops, it is hard to say how long the crisis can be sustained and yield an outcome favorable to the West. Putin can’t keep all of his battalions mobilized through 2022 – or can he?

If President Putin were to gradually drawn down troop levels, then a withdrawal of, say, half the Russian troops from Ukraine’s borders by summer might be counted as a Western strategic victory. But we suspect that any resolution to the crisis will require more than NATO “not blinking” and any short-term expedients so employed will not hold for long.

PLAYING THE LONG GAME

Set against this backdrop, Greymantle counsels caution, compromise, and a view toward ‘the long game’.

The U.S. should make good use of the Ukraine stand-off to offer Russia a tantalizing olive branch: good faith negotiations on nuclear arms control, non-proliferation, navigation of Arctic waters, conventional land-based missile systems deployed in Europe, and establishing a joint framework for how to wage cyber-warfare.

Technological advances are once again altering the rules of warfare. Now would be a good time to establish new norms regarding the use of both old and innovative forms of weaponry.

By offering a potential settlement on Ukraine that would leave Russia’s western neighbor out of NATO, the U.S. and its allies may avert short-term havoc, draw Mr. Putin to the negotiating table, and buy badly needed time to catch up on hypersonic missile technology, rebuild NATO’s battlefield capabilities and get their own political houses in order.

Reaching a strategically ambiguous settlement may still be possible. The U.S. reach an ambiguous settlement re: Taiwan with China in the early 1970s. The resolution of 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis also involved a highly ambiguous settlement that allowed both the U.S. and Soviet Union to deescalate. The U.S. could pursue a similar deal on Ukraine.

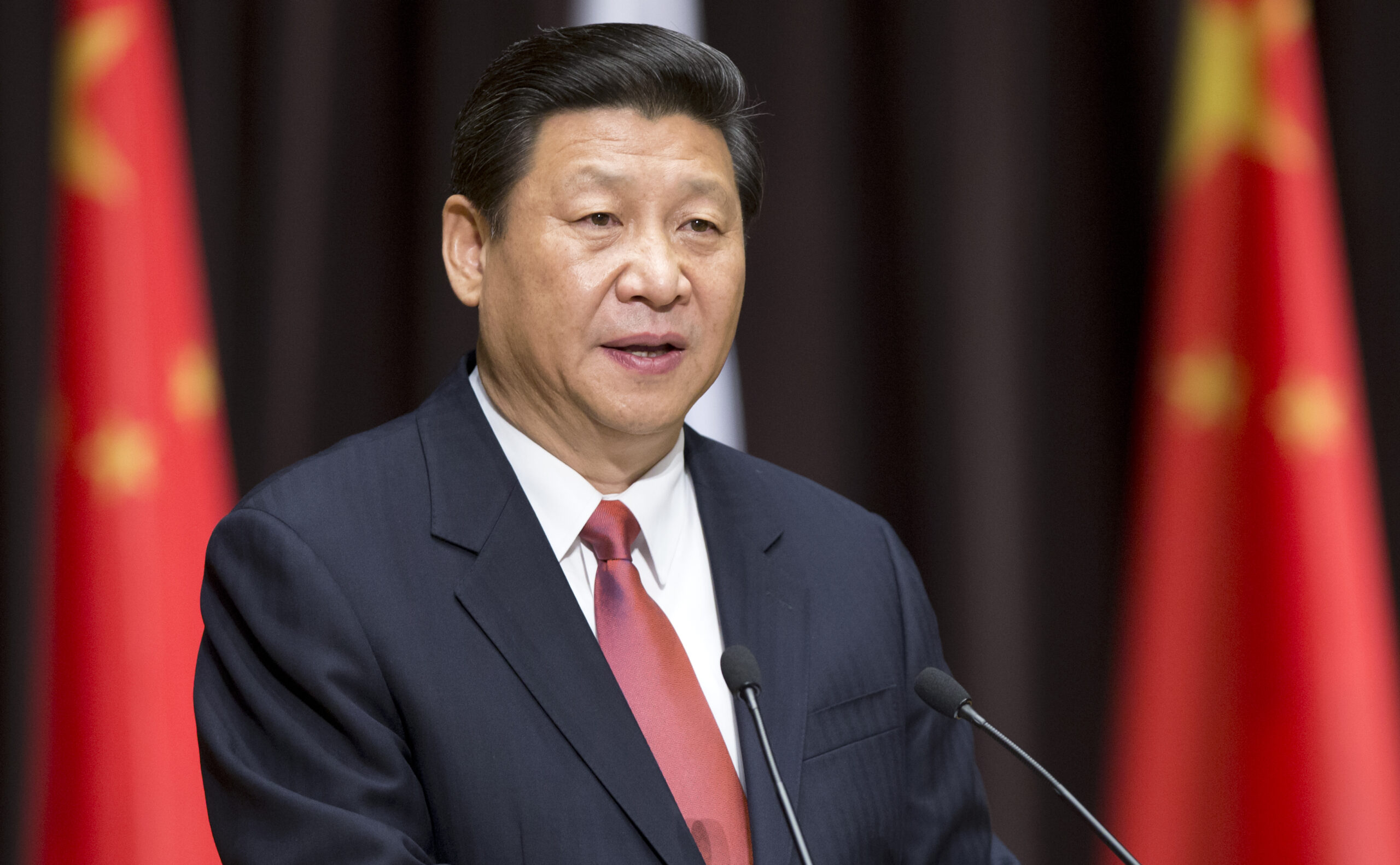

More importantly, drawing Mr. Putin into a lengthy round of negotiations will buy the West time vis-a-vis Mr. Putin himself. The Russian leader will turn 70 years old this October. Though he is, by all accounts, in remarkably good shape and keeps to a strict health regimen, very few Russian leaders have lasted past age 75.

Being a leader who rules Russia by virtue of his indispensable personality and considerable talents (and fear), Mr. Putin is setting his homeland up for a bear of a succession crisis when he finally leaves the scene. Until that happens, the U.S. is going to have to play its cards very adroitly, carefully setting the stage for how it will deal with Mr Putin’s successors.

Until next time, I remain –

Greymantle