|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“To be woke is to be alive to the interlocking systems of oppression that shape our world.” — Robin DiAngelo

“White comfort maintains the status quo.” — Ibram X. Kendi

“Trans women are women. That’s it.” — Popular activist slogan

In a society awash with slogans, hashtags, and moral imperatives, the term “Wokism” has emerged as one of the more slippery entries in the contemporary political lexicon. For some, it represents an overdue moral awakening to the injustices baked into American life. For others, it signals the rise of a new orthodoxy—cloaked in compassion, fluent in the language of rights and inclusion, but with the instincts of a revolutionary vanguard.

But what is wokism, exactly? Where did it come from? And why does it make so many people feel vaguely uneasy, even when they agree with some of its stated goals?

This Greymantle post is an attempt to chart the winding intellectual and cultural rivers that have merged into the current delta we might call “Social Justice Ideology” (SJI)—or “Wokism,” for short. It is neither a diatribe nor an endorsement. Rather, it’s a kind of field guide—for the perplexed, the curious, and the quietly alarmed. Hence the title of our post: “Understanding Wokism: A Guide for the Perplexed.”

I. Introduction: The Great Confusion

In 2020, after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the explosion of racial justice protests across the United States, many Americans found themselves confronted by a moral and cultural vocabulary they had never heard before—or at least, had never heard used in quite this way. Words like “privilege,” “microaggression,” “allyship,” “systemic racism,” and “lived experience” suddenly took central importance in public life.

These aren’t just buzzwords: they are the moral grammar of a worldview that has already taken root in universities, activist circles, corporate diversity offices, and media institutions. The label that emerged in 2020—first as a pejorative, then with begrudging acceptance—was “woke.”

For some, wokism represents long-overdue moral progress. For others, it is a betrayal of liberal ideals: a turn toward moral absolutism, censorship, and racial essentialism.

Yet even among critics, there has often been confusion. What exactly is wokism? Is it a new cultural ideology, a religion, a style, a sensibility? Is it the new Civil Rights movement…or a repudiation of the old one? If you’re confused, then you’re not alone.

II. What Is Wokism?

To understand Wokism, one must first resist the temptation to view it as a single, tightly defined ideology. It is not a new Marxism, nor a religion, nor even a coherent political program. It is, rather, the confluence of several postwar liberation movements and intellectual currents that began to merge—somewhat uneasily—in the last quarter of the 20th century.

Let’s begin with a working definition: Wokism, or Social Justice Ideology (SJI) is a worldview rooted in the notion that social life is structured by systemic oppression—particularly along the lines of race, gender, sexuality, and other categories of identity—and that moral virtue requires identifying, dismantling, and reimagining those structures.

The ideology blends academic theory, activism, and therapeutic language into something that feels both righteous and oddly performative. Its proponents insist they are dismantling power; its critics say they are merely redistributing it in new, more sanctimonious forms.

III. Many Rivers, One Floodplain

To arrive at a clear understanding of SJI, it is often helpful not to treat it as a single, coherent doctrine, but as the result of a confluence—a convergence of ideological rivers that began flowing during the 1960s and gradually merged between the late 1980s and early 2010s into a “Movement of Movements”.

Wokism tends to take up the moral concerns of Civil Rights-era liberalism—especially racism, sexism, and anti-gay prejudice—but it filters them through a distinct set of assumptions: that all social life is structured by systems of power; that identity is more foundational than individuality; that speech is violence and silence is complicity; and that the pursuit of justice requires not neutrality, but active disruption of oppressive norms.

Wokism is often described as “neo-Marxist”. But this label is misleading, because wokism is not primarily focused on class, the proletariat or economic redistribution. Rather, its focus is cultural and psychological. Its units of analysis are identity groups. Its terrain is language, representation, and institutional power.

The moral framework of wokism is highly idealistic and deeply emotionally charged. It demands moral purity, assigns collective guilt, and prizes authenticity and trauma.

As a worldview, it borrows from postmodernism, postcolonial theory, critical race theory, intersectional feminism, and queer theory. As a movement, it has fused together formerly separate causes—Black Lives Matter, gay rights, transsexual/transgender rights, feminist activism, anti-colonialism, indigenous politics, disability rights—into a broader crusade against what it defines as ‘systemic oppression’.

This is why it makes sense to call Wokism a “movement of movements.” Think of it as the confluence of several rivers that ran along their courses for some time before converging into a single, fertile river delta.

IV. The 1960s: The Seeds of a Sensibility

Wokism’s intellectual genealogy can be traced back to the late 1960s. The 60s were a time of moral awakening and generational rupture in the United States. The initial postwar social consensus began to unravel, and with it came an explosion of new social movements (NSMs) — civil rights, second-wave feminism, gay liberation, anti-war protests, and more.

These new social movements began by confronting concrete prejudices and unequal legal treatment for certain groups—racial segregation for Blacks, sex-based discrimination against women, intractable poverty affecting a number of social groups—but over time, their focus expanded. They began to interrogate not only the law but the very basis of American society. The personal, as the saying went, became political.

One of the earliest and most powerful tributaries feeding into the river delta that would give birth to woke cultural ideology was the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, particularly as it evolved beyond the integrationist vision of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and into a more radical, identity-based politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The early civil rights movement—led largely by Christian and Jewish clergy—had pursued legal equality and racial integration under the terms set by the U.S. Constitution. But out of the civil rights movement, a more radical current emerged—Black Power – a movement centered on groups who viewed American liberal democracy itself with skepticism or even outright hostility.

The women’s movement, too, began by pursuing legal equality but evolved into a deeper critique of patriarchy as a ‘system of control’ embedded in everything from language to labor markets to family dynamics. Out of this critique came second-wave feminism, which by the 1980s fractured into various competing schools of thought ranging from liberal feminism to radical separatism, each with its own vocabulary of patriarchy, oppression, and resistance.

V. The Age of Movements

Along with Black Power and second wave feminism, four additional currents emerged during this period that would greatly influence the development of wokism:

- The Radical New Left. Groups like the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Black radical student organizations, and eventually the Weather Underground rejected liberal reformism in favor of anti-imperialism and Marxist revolution. Some members fled to Canada or went underground. But many eventually returned to academia, earning PhDs and becoming what Roger Kimball called “tenured radicals.” Figures like Bill Ayers and Angela Davis exemplify this trajectory: revolutionaries turned professors who imported radical politics into the curriculum of American colleges.

- French Poststructuralism. In the 1970s, ideas from French thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida began to infiltrate American academia. Foucault in particular had a lasting impact with his theory that power is diffuse and embedded in discourse. Deconstructionism, with its emphasis on language and meaning, destabilized traditional liberal categories like truth and objectivity. These ideas slowly took hold in literature, gender studies, and cultural studies departments throughout the 1980s.

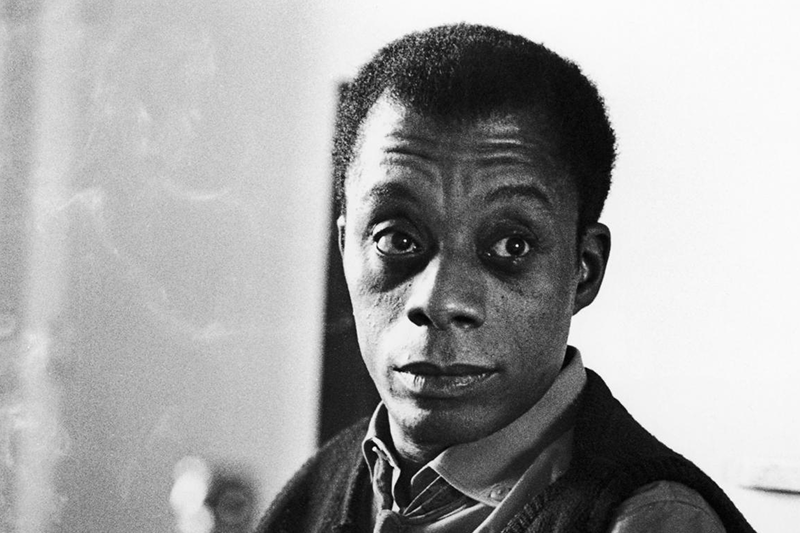

- The Gay Rights Movement. After Stonewall in 1969, the gay rights movement grew increasingly visible. Though initially separate from Black activism and feminist movements, gay intellectuals like James Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni helped establish shared discursive ground. Being both Black and gay—and often, like Baldwin, deeply ambivalent toward the American liberal project—they laid the groundwork for a more matrix-like form of resistance that would flower in later decades.

- Anti-Colonial Theory and Movements. Influenced by thinkers like Frantz Fanon, the Martinique-born psychiatrist and anti-colonial theorist, a new generation of activists came to view oppression as a psychological and ontological condition—one that deformed both the oppressed and their oppressors. “The colonized man is an envious man,” Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth. Fanon’s diagnosis of colonialism as a cultural virus—one that could only be expunged through violence or rupture—would leave deep marks on later forms of identity-based activism.

Taken together, these six rivers—Black Power, second wave feminism, radical left-Marxist politics, postmodern theory, gay identity-based liberation and anti-colonial theory—continued to flow separately through the 1970s and 1980s, even as American college campuses quieted down following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975.

James Baldwin in the early 1960s

VI. The Academy as Refuge: Late 1970s–Early 1990s

As American politics in the 1980s swung to the right in under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, many on the left turned inward. Universities became a sanctuary: a place to regroup, theorize, and reframe their moral vision in more abstract, scholarly terms. Conservative critics often describe this period as the beginning of the American Left’s ideological “long march through the institutions.” But for the activists themselves, it felt more like a resistance in exile.

Black intellectuals who emerged from this period include the aforementioned Angela Davis, along with bell hooks and Cornel West. Each of these thinkers critiqued capitalism, patriarchy, and imperialism all at once, framing Black liberation as inseparable from all other ideological struggles of the global left. Audre Lorde, a Black lesbian feminist and poet, helped pioneer the idea that identity categories were not only political battlegrounds, but sources of moral authority.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” Lorde declared—an assertion that became central to the later doctrine of intersectionality.

At around the same time there arose queer theory, a doctrine that rejects the idea of stable gender or sexual categories altogether, offering instead a kind of metaphysical improv jazz around sex, gender and personal identity. Its most notable evangelist was and is Judith Butler.

In Gender Trouble (1990), Butler advanced the idea that gender is not a biological fact but a social performance—an identity enacted, reinforced, and naturalized through repetition. It is a deeply destabilizing idea: if gender could be performed, it could also be reimagined.

Butler’s language is famously impenetrable – the French post-structuralists were a source of inspiration – but her ideas seeped into academic and activist thought, becoming gospel in gender studies and the later intellectual scaffolding of trans activism. If Wokism has saints, then Butler is its Saint Augustine—a metaphysician of the postmodern soul.

Judith Butler in the late 2010s

After queer theory came disability rights, fat acceptance, and eventually the sprawling galaxy of intersectionality—a concept originally devised by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe overlapping forms of discrimination. It emphasizes how several varieties of oppression (e.g., race, gender, class) interact in the lives of ‘marginalized’ people, and has since taken on an almost theological flavor among people with progressive belief systems.

Overlaying all these developments was a growing academic trend—first in literary studies and later in sociology, education, and even medicine—to embrace postmodernism and critical theory. These belief systems emphasize the socially constructed – rather than the fact-based or scientifically testable – nature of knowledge, the pervasiveness of power in all relationships, and the need to “problematize” virtually everything, from the Enlightenment to peanut butter.

Academic departments—especially in the humanities and social sciences—became increasingly dominated by poststructuralist and identity-based frameworks. Identity was no longer a personal attribute; it was a structural location within a web of power. The result? A worldview that treats identity as the primary axis of justice, language as a site of political struggle, and power as omnipresent and invisible—except, of course, when it’s being exercised by the powerful against the marginalized.

VII. The 1990s-2000s: Professionalization and Consolidation

Between the First Iraq War (1990-91) and the Global Financial Crisis (2007-08), a broad social convergence – a cross-pollination of ideas and alliances of the like-minded — among different American ‘out groups’ began to occur. More importantly, by the mid-1990s the social justice movement (as it was starting to call itself) was no longer content to merely hibernate and theorize in exile—it began professionalizing and planning for the future.

Activist scholars moved out of the classroom and into non-governmental organizations (NGOs), human resources departments, and nonprofit foundations. The language of critical theory became bureaucratized. It was adopted by university administrators, HR consultants, and grant writers. Identity-based grievance, once radical, became institutional.

Diversity training workshops began to proliferate. Universities created bias response teams. Terms like privilege, microaggression, and systemic racism, still used only by a small fringe of committed activists, began their steady march into the professional class’s vocabulary.

This period saw the early stirrings of what critics would later call “institutional capture”—the process by which social justice ‘frameworks’ began to displace liberal principles within large institutions, particularly the notion of viewpoint neutrality. The goal was no longer fairness despite identity, but fairness through identity—a subtle but profound shift.

VIII. The Great Convergence: 2010-2015

The early 2010s witnessed an ideological Big Bang. Various tributaries of activism—Black Lives Matter, transgender rights, climate justice, body positivity—began to coalesce into a single river: a coherent cultural force superficially resembling a unified ideology.

The term “woke,” originally African American vernacular for social awareness, was absorbed into a broader belief system that no longer simply observed inequality but prescribed an ever-growing set of rituals, norms, and policies to remedy it.

Key texts provided the ideological substrate. Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility (2018) argued that white people are inherently defensive when confronted with their racism, and that their discomfort is itself evidence of guilt. Ibram X. Kendi, in How to Be an Antiracist (2019), went further: “The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination,” he wrote. “The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”

One of the most influential figures during this period was Ta-Nehisi Coates. A once-liberal Black writer who became radicalized over the course of the Obama years, Coates’s 2015 book Between the World and Me articulated a bleak, unyielding view of America as ‘structurally’ white supremacist.

In his writing for The Atlantic, Coates helped reframe racism as not merely a historical wound but a defining feature of American life—inescapable and unending. His influence on elite discourse, particularly among young white liberals, cannot be overstated.

IX. The Explosion: 2015–2020

In the second half of the last decade, three major developments transformed this accelerating ideological convergence into a truly eruptive and assertive social movement:

- Social Media. Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, and later TikTok served as organizing tools, educational platforms, and disciplinary mechanisms. Hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo transformed individual grievances into collective action. Cancel culture emerged as both a tactic and a signal: dissent would not be tolerated.

- The Election of Donald Trump. To many in the emergent woke coalition, Donald Trump literally embodied every axis of oppression: whiteness, maleness, wealth, transphobia, Islamophobia, misogyny, etc. Opposition to him provided a sense of unity. Criticism of Trump became a loyalty test.

- The George Floyd Protests. The killing of George Floyd in 2020 was a catalyst. Protests erupted globally. Corporate statements poured in. Books like White Fragility and How to Be an Antiracist topped bestseller lists. Suddenly, wokism was no longer subcultural. It had become the default moral language of every major institution.

The role played by social media was critical here. Hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #TransRightsAreHumanRights allowed disparate groups to rally under a common moral grammar, even if their immediate concerns differed. Suddenly, phrases like “structural racism”, “white fragility”, and “decolonize your bookshelf” were being used unironically by people who had never read a page of Frantz Fanon.

By 2020, the Pride Flag—redesigned into a progressive, inclusive banner including trans and non-binary stripes—became the symbolic standard of this coalition. Gender identity supplanted biological sex in institutional policy. Terms like “Latinx,” “birthing person,” and “cisgender” entered official usage. Youth gender medicine, once experimental, became defended as a ‘fundamental human right’ by activists and medical associations alike.

Institutions rushed to adopt this new worldview. Corporate DEI programs exploded. Prestigious universities denounced their own histories. Journalists lost jobs for tweeting the “wrong” opinion. Even hard science suffered from the contamination of whiteness and colonial logic.

The woke vision marked a departure from traditional liberalism. In the name of justice, neutrality was reframed as complicity. Colorblindness became a form of erasure. Debate was replaced by reeducation. Ironically, it was not dissimilar from earlier revolutionary ideologies—except instead of class consciousness, one had to cultivate racial or gender consciousness.

X. The Critics Speak

But Wokism’s cultural hegemony is fragile. Starting in the early 2020s, a growing backlash has emerged—not just from conservatives, but from liberals and some elements of the Old Left.

J.K. Rowling’s critiques of gender ideology, Andrew Sullivan’s defense of liberal universalism, and Jesse Singal’s investigative work on youth gender medicine all broke taboos. Polls showed that even many liberal voters were uncomfortable with some of the new orthodoxies.

The alliance between anti-racism and gender radicalism proved especially combustible.

The idea that men could become women simply by self-identification—not only socially but legally and medically—clashed with biological realities and common intuitions. The phrase “woke gone too far” became shorthand for a deeper sense that something important had been lost: a shared basis for public reasoning.

Additionally, not everyone was impressed with SJI’s underlying thought structure.

Wesley Yang, a Korean-American writer and critic, coined the term “successor ideology” in 2021 to describe wokism’s ascendancy—an ideology that had supplanted liberalism in elite institutions under the guise of social justice. It was, he argued, a politics of psychological safety that sought to transform not just policy but language, memory, and thought itself.

Christopher Rufo, a conservative activist and intellectual descended from Italian communists, took a more combative approach. He spearheaded efforts to ban Critical Race Theory in public education and warned that woke ideology was “an existential threat to the American way of life.” Rufo’s work has been accused of alarmism—but he has also effectively shown how radical ideas incubated in universities end up reshaping corporate and governmental policy.

Centrists, too, have voiced concern. Yascha Mounk, in his 2022 book The Identity Trap, describes wokism as an intellectual bait-and-switch. It begins with plausible concerns about discrimination, then shifts to a rigid worldview that sorts people by group identity, punishes dissent, and promotes authoritarian solutions in the name of liberation. “It is a vision that undermines liberal values,” Mounk writes, “and offers a dismal future of social balkanization and permanent moral panic.”

XI. The Language of Kindness, The Politics of Power

One of the paradoxes of Wokism is that it speaks the language of empathy while operating as a power project. Its tools—public shaming, cancellation, bureaucratic enforcement—are not gentle ones. Its underlying logic is revolutionary: institutions must be “decolonized”; speech must be policed for safety; society must be reengineered until equity is achieved.

Wokism speaks in the idiom of empathy, inclusion, and “lived experience.” It exhorts us to be kind, to listen, to ‘believe the women’ and the claims of other ‘marginalized’ groups uncritically. Its memes and TikToks are full of warm pastel colors and talk of healing and affirmation. But its actions, especially when it comes to dissent, often tell a very different story.

Debates are policed, heresies punished, and critics labeled in moral terms: racist, sexist, transphobic, complicit. It is a political project that, for all its pacifist aesthetics, is deeply concerned with power—who has it, who doesn’t, and how it can be redistributed or deconstructed entirely.

The Israel-Palestine conflict offers a recent case study. What was once a complex geopolitical tragedy has, within Woke discourse, been reframed as a morality play: one side is “oppressed,” the other “colonizers.” In this schema, nuance is not just unwelcome; it is viewed as a form of complicity. The result has been a surge of aggressive rhetoric—occasionally spilling over into outright threats and harassment—all justified under the banner of ‘justice’.

Perhaps most crucially, this ideology presents itself not merely as an opinion or a movement, but as a form of moral clarity. To be “woke” is not just to have a certain view of the world—it is to have seen the truth. And once seen, one cannot unsee it.

XII. What It Is, and What It Isn’t

Let us be clear: to critique Wokism is not to deny that racism, sexism, anti-gay prejudice, and other unpleasant realities exist. Nor is it to long for the good old days when nobody used the word “problematic.” The world has been changed, occasionally for the better, thanks to some of the movements that gave rise to today’s SJI and the modern cultural shifts they engendered.

The problem is not the existence of social movements, but rather the emergence of an ideology that treats certain movements as beyond criticism—immune from irony, allergic to dissent, and increasingly comfortable with coercion. It is the slow shift from fighting for equal rights to enforcing ideological conformity. And it is the tendency to measure progress not by actual outcomes, but by the public performance of moral alignment.

Not all of Wokism’s goals are entirely without merit. Racial prejudice is real. Gender norms can indeed be stifling. Compassion matters.

But wokism has transformed these concerns into a strict dogma, with heretics and sacraments to match. It has become what the historian Robert Conquest once called a “moral economy of guilt”—where status is measured by one’s acknowledgement of inherited sin and willingness to perform ideological penance.

XIII. Conclusion: Toward Clarity and Caution

Where Wokism goes from here remains unclear. Will it entrench further in elite institutions, or provoke a larger cultural reversion? Will its language continue to evolve, or has it peaked? These are open questions. For the perplexed, the first step is to recognize its genealogy—not to caricature it, nor to dismiss all those who speak its language, but to understand what it is, where it came from, and where it wants to take us.

Wokism, like many belief systems that came before it, began with real grievances and sincere hopes. Like all ideologies, it contains truths, half-truths, dangerous oversimplifications and outright falsehoods. It arose from righteous anger at genuine injustices—but has evolved into a sprawling movement whose revolutionary goals are guised in therapeutic language.

In its current form, Wokism seems to demand not only agreement but submission. Its tone is therapeutic — its methods, increasingly authoritarian.

Still, Greymantle believes that it’s important to not overreact.

Wokism is not a totalitarian regime (at least not yet), and its excesses often collapse under their own internal contradictions. Like all powerful ideologies, it thrives on the fear of being called out and the hope of being seen as good.

Wokism is, in that sense, a mirror of the society it seeks to transform—deeply moralistic, status-driven, and anxious about the future.

Until next time, we remain —

Greymantle