For the eight decades since World War II, Americans have confidently believed their nation boasts the largest navy on earth and that it dominates the world’s seas. Half of that belief is no longer valid, and the other half may now be debatable.

Beijing presently commands the world’s most significant number of warships, supplemented by a potent coast guard, while also floating a gigantic commercial fleet. Every year, China’s shipyards launch about 20 times the number of seagoing vessels the United States can construct in that time.

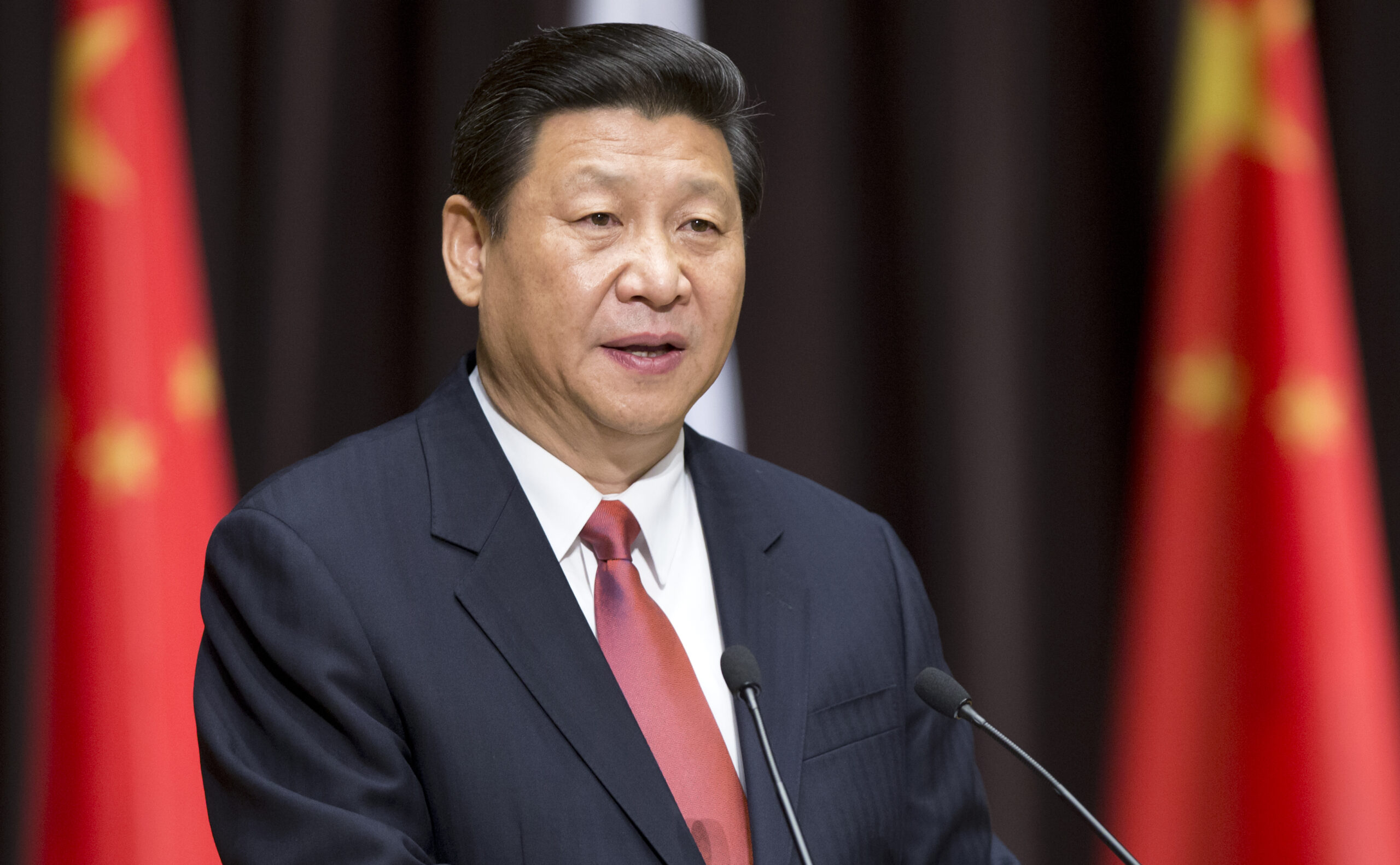

Perhaps we weren’t paying close attention while we pursued our prolonged War on Terror — charging up mountains and through deserts and suchlike over the last 25 years. During this time, Chinese leaders have been steadily upgrading their naval force and their missile capabilities.

The Chinese navy (officially, “the People’s Liberation Army-Navy, or PLAN) no longer functions as a mere riverine and coastal appendage of the army; it is now a “green water” armada easily capable of ruling the East and South China seas.

Beijing’s navy is being shaped to do the following: (a) to keep the enemy (us, by the way) from its shores and Taiwan’s; (b) then to control that island, one way or another; (c) to secure its vital commercial sea lanes across the Indian Ocean to the homeland; and (d), as just mentioned — to eventually push the United States Navy (USN) out of the Western Pacific.

The burning question is whether China’s navy has already become capable of achieving these goals through its methodical naval modernization and vigorous fleet expansion.

CHINA’S NAVAL ASSETS

There are several estimates of the exact number of “battle platforms” Beijing commands. Also, this disparity of agreement about the arithmetic exists partly because different measures are applied to different ship classes at various times. In 2022, for instance, the U.S. Department of Defense tallied 370 battle platforms in China’s naval inventory.

Another respected source is the “World Dictionary of Modern Military Warships.” For 2024, it concluded that the PLAN’s fleet comprised 427 vessels, mostly because it included many lighter patrol craft.

Only some researchers believe that all these smaller craft are meant to operate in the open seas.

The most recent report on the PLAN was published in mid-2024 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). This commentary, entitled “Unpacking China’s Naval Buildup” states that China operates 234 fully operational sea-going warships.

The authors explain their reckoning: “This count of China’s fighting ships encompasses all of its known, active-duty manned, missile- or torpedo-armed ships or submarines displacing more than 1,000 metric tons, including the 22 missile-armed corvettes recently transferred to the China Coast Guard but not the approximately 80 missile-armed small patrol craft operated by the PLAN. The CSIS total includes significant surface combatants, submarines, and ocean-going replenishment auxiliaries.

DESTROYERS: Other than carriers, China’s largest warship is the Type 055, which runs 12,000 tons, making it less of a large destroyer and more of what Western navies typically refer to as a light cruiser. (The USN’s destroyer mainstay is the Arleigh Burke class; it averages 8,300 tons.)

It should be noted that America’s heavier battle platforms can carry more missiles and other weapons than the PLAN vessels of the same class. For the USN, these other weapons include anti-air and anti-submarine defenses. USN vessels can remain longer at sea, and they can absorb more punishment. Most of these, however, are a few decades older than 70% of China’s recently built warships.

A preceding Chinese destroyer class is the 052. The latest variant is the 052D, which displaces 7,500 tons and features 64 vertical launch cells. These can fire the supersonic YJ-18 anti-ship missile between 220-600 km. There are 28 of these warcraft (with three more reported to be under construction as of March 2023, so potentially completed as of this writing.)

FRIGATES & CORVETTES. For decades, the Chinese have put several classes of indigenously built frigates into service, which could be described as light cruisers by Western estimates. Averaging about 4,000 tons, they are designed to perform the same deep-water missions as their larger cousins, and thus they are armed with the same weapons. Also, these vessels can support rotorcraft. Frigates can easily sail with a sea-going fleet or operate independently. Most reports presently count 43 of them.

Corvettes are light frigates. The newest classes displace 1,300 to 1,500 tons. Their relatively compact hulls can handle blue waters, but their shallow drafts also prove helpful in tasks closer to shore. Corvettes’ missile-based combat capabilities are, of course, less considerable.

Almost 16% of these hulls fill out PLAN’s warship array. America has never invested in such lighter craft outside its Coast Guard, seeing little value in fighting close to its coast. Nevertheless, China’s numerical superiority of quickly constructed warships bolsters its claim to have the world’s most oversized (i.e. the largest) navy. The latest count is 71 corvettes.

SUBMARINES. There are several types to consider. China’s nuclear ballistic missile carriers, or SSBNs, are strategically vital. About 6 of these exist, and their 12 missiles can reach many western U.S. targets. Next in significance are nuclear attack subs, which often escort the SSNBs or perform various offensive duties. PLAN can also boast 4 SSNs.

The vast majority of its underwater fleet (55), however, are diesel-electric attack boats, which have a more limited range and generally tend to be noisier (i.e. more easily detected with SONAR). Nevertheless, they are helpful in the adjacent South China Sea.

The American Navy has a definitive advantage in this category of sea power. It is divided into SSBNs and attack subs. (One SSA is assigned to each carrier task force.) Almost all of its 53 boats are nuclear-powered, which gives them more range, greater lasting power on the station, and lesser detectability than China’s underwater force. They can also carry out land assault missions with their cruise missiles and perform many other duties.

AMPHIBIOUS SHIPS: One estimate credits PLAN with 37 amphibious ships, including three helicopter carriers. Another source lists just 11. Lately, much attention is being paid to a carrier-like vessel being built in the Guangzhou Shipyard. It is almost the size of a carrier, but still appears a bit too small. This ship may be intended for amphibious purposes, drone launches — or both.

AIRCRAFT CARRIERS: This class of ship is the most significant indicator of Beijing’s intentions. Besides the United States, no other nation spends enormous time and resources constructing aircraft carriers. After all, many believe China’s super-duper missiles have made these relics of the Cold War obsolete — right? They are just old-fashioned imperial enforcers of weak countries that border an ocean — right?

Perhaps.

It is evident that China does not agree with the above assessment. We can observe its slow but meticulous assembly of aircraft carriers and its naval pilots’ training. The obvious conclusion is that Beijing’s grand strategy includes eventual sea control of open waters, which only the United States now has among all world powers.

Such floating airbases are vital to forming a powerful air-sea task force that can rule any sea far outside the ranges of China’s land-based missiles or aircraft. There is only one way to rule a sea zone nowadays with airpower present, however many missiles you can launch, and that is with a carrier force. And of course, every carrier task force has a submarine escort or two.

A fourth Chinese aircraft carrier is in the works. Each new one deploys more planes. China’s future carriers do not appear to be intended to oppose the USN directly, but to deny a lesser force (e.g. the Indian or Vietnamese navies) access to regional sea control…if America’s strength is absent.

We must also remember how land-based missiles and airpower greatly enhance China’s maritime clout. The longest-range, truck-mobile anti-ship weapon in its commodious arsenal is now the D-26, which can reach 1,620 or 2.160 nautical miles. (Some older intermediate-range models don’t travel so far; these, however, could still pound our major island bases in Guam and everything in between.

There are also many People’s Liberation Army Air Force aircraft — some of them fourth- and fifth-generation fighters. Bombers fitted with anti-ship cruise missiles are on call. Once again, the supplemental damage they can do at sea, in aggregate, rises as a foreign fleet’s proximity to China narrows. The United States would likely match any naval air assets that Beijing could apply, at least away from the first island chain.

CONCLUSION – THE CHINESE NAVY IS A FORMIDABLE CHALLENGER TO THE USN

This brief review of its assets shows that the PLAN is now a formidable challenger to the USN and all other major naval forces. Nevertheless, the PLAN’s numerical superiority in overall vessels does not automatically guarantee it high-sea dominance.

Every admiral knows, however, that more of the right kind of warships, at the right time and place, usually give him/her more options.

According to most sources, the American Navy of 2024 commands 290-292 battle platforms as its core. At any one time, maybe a third is being rotated through cycles of crew rest, repairs, upgrading, or replenishment. Available vessels are distributed globally; however, China’s are concentrated in the Western Pacific, making their rotations shorter. It’s clear that the incoming Trump Administration is going to have its hands full countering Chinese naval power in the Pacific.

Alliances also cannot be ignored. The Chinese have already been coordinating naval exercises with Russia’s eastern squadrons. North Korea’s minor contribution could supplement the partners here. Balancing this for the Americans are the considerable naval and air forces of Japan, Australia, and South Korea, at the least. The Philippine navy could also contribute in a number of ways.

A valuable measure of firepower is a simple count of VLSCs (or vertical launch system cells) when comparing fleets. China has an impressive array of anti-ship and defensive missiles that can fire extensive ranges from these shipboard tubes. Most are comparable to Western models.

The CSIS has compiled a chart illustrating Beijing’s steady progress in narrowing the gap, and the Institute’s calculations indicate that China’s navy will close it this year or the next.

The top goal of PLAN’s firepower is to kill or wound a U.S. carrier and its accompanying task force. This is not easy, and the process of pinning down the target in the vast Pacific Ocean would begin in space. Observational satellites are essential, so the Chinese (and the Russians) have both been developing what appears to be counter-spacecraft to seize or maim our orbiting spies.

IS CHINA’S NAVY READY FOR ‘BLUE WATER’?

Admittedly, there needs to be more discussion of the American Navy’s advantages and China’s disadvantages. The latter tend to be inexperience in combat, erosive corruption, scarcity of workforce, and insufficient logistics to sustain “blue water” aggression in the center of a broad ocean. Also, America’s very quiet nuclear attack submarines presently appear superior to the PLAN’s (largely diesel-powered) underwater force in capabilities and training, if not sheer numbers.

Nevertheless, it is clear from this review that the U.S. Seventh Fleet can’t risk pushing beyond the First Island Chain to close in on China’s coast, even with the help of Japan and South Korea. Beijing has chosen to emphasize lighter warships and missile warfare to achieve this regional power. Consequently, PLAN is shaped to be most beneficial for “green water” combat that can benefit from land support.

Beijing is still in the early stage of carrier development. The goal is not to compete directly with America’s platforms — that’s what anti-ship missiles are for — but with every other navy.

China intends to soon develop the capability of putting a powerful carrier task force in the middle of an ocean it wants, as the United States does now. To do that– to keep a carrier task force on station in a far sea– takes enormous resources and sufficient relief and supply escorts.

But the PLAN is working on it.

On May 2nd this year, the government announced that its third carrier, the Fujian, had begun sea trials. There was a bit of chest-beating because this new vessel is comparable to the United States’ size, aircraft load, and technology. It has an electromagnetic catapult to speed up plane launches. The two earlier ships were modeled on Soviet designs and were intended for pilot training.

The Chinese did not hide their plans. “With the official commissioning of Fujian, the navy will transition into a ‘three carrier era,’ facilitating a rotation system where one carrier can undergo repairs, another can maintain training readiness, and the third can engage in combat training. This strategic deployment enables the PLAN always to ensure the presence of an aircraft carrier in strategically important sea areas.” Protecting their commercial sea lanes is part and parcel of that carrier’s duties.

It’s no surprise that there is a sister-ship to Fujian in the works (not to mention that unusual smaller one, which may be for drones or attack helicopters — or both).

Blue-water dominance?

America may have that dominance now, but the sails of a very determined competitor are showing white over the horizon.

Richard Jupa is a former naval officer. He has published a book on the First Gulf War, as well as more than a dozen articles on current military matters or military history. He lives in New York City.