|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

PART I: WHY DEMONIC HORROR WON’T STAY BANISHED

The devil never really leaves.

If you’ve been paying even a modest amount of attention to horror films over the last fifteen years, you may have noticed something uncanny: demonic possession is back.

To be fair, it never really vanished. But since the late 2000s, and especially after the breakout success of The Conjuring in 2013, exorcism-themed horror films have returned to the cultural foreground with a consistency and intensity that feels almost…ritualistic.

Whether it’s The Last Exorcism (2010), The Rite (2011), The Devil Inside (2012), Deliver Us From Evil (2014), The Vatican Tapes (2015), The Possession of Hannah Grace (2018), Prey for the Devil (2022), or the 2023 reboot The Exorcist: Believer, the genre has refused to – if you’ll pardon the pun – exorcise itself from our screens.

Even independent and psychologically tinged horror entries like At the Devil’s Door (2014) and The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014) have dipped into possession territory, updating the theme with modern anxieties, new settings, and occasionally subversive twists.

Additionally, a new subgenre of Jewish-themed possession and exorcism-themed films including The Dybbuk (2019), The Vigil (2019) and The Offering (2022) has recently emerged within this cinematic space, broadening the scope of its cultural interest and concern.

This isn’t merely a matter of horror recycling its own tropes (though that happens too). Instead, what we’re seeing is a sustained resurgence of demonic possession and exorcism as dominant aesthetic motifs, both in mainstream studio horror films and indie cinema.

This phenomenon merits closer attention. Why are early 21st century audiences so drawn to tales of innocent people overtaken by supernatural evil? Why do filmmakers keep revisiting the same mythologies of fallen angels, tormented clergy, and beds that levitate? In this post, we shed some light on what the surge in exorcism movies says about America.

SELLING THE DEMONIC

One answer is the simplest and most prosaic: exorcism sells. It’s about the money.

Horror has always offered high return-on-investment opportunities for film studios, and exorcism-themed horror has developed into a reliably bankable subgenre since the late 2000s. The exorcism subgenre retains broad audience familiarity while requiring relatively modest budgets and easily recognizable motifs—flashing lights, screaming girls, crucifixes, foreign languages uttered in guttural voices, etc.

But the staying power of the genre can’t be explained by its commercial viability alone. If it were merely a matter of profit, then the exorcism horror wave would have experienced a short burst in the late 2000s and early 2010s and then faded away. Instead, we seem to be witnessing a sustained cultural reflex extending well into the 2020s.

If you’re skeptical, then just log onto Netflix or any other streaming service. Toggle down to the “horror” choices and browse through them: about one in four is a demonic or possession film.

IS THE DEVIL REAL—OR JUST GOOD BUSINESS?

In the early 2000s, demonic and exorcism-themed films constituted a relatively minor horror subgenre, and a rather fringe and dated one, at that. By the turn of the century, The Exorcist and its sequels were considered old hat. Horror movies in the 1980s and 90s were dominated by slasher films and creature features such as the original Alien (1979) and its spin-offs. Nobody expected demonic possession films to make a comeback.

The exorcism subgenre was reinvigorated starting in the mid-2000s by films such as Constantine and The Exorcism of Emily Rose (both 2005), which were notable in that the first was inspired by an underground comic book series, Hellblazer, created by British author Alan Moore – an example of an artist creating his audience if ever there was one – while the second was inspired by a purpotedly real case of exorcism in Germany that occurred in the mid-1970s.

Constantine and Emily Rose were sleeper hits notable for re-establishing the commercial viability of the subgenre. More exorcism-themed movies (e.g. The Last Exorcism) soon followed. By the mid-2010s, the success of The Conjuring (2013) and its spinoffs revealed that exorcism-themed films could deliver strong box office returns on relatively modest budgets. The studios quickly figured out that they had struck gold.

The loyalty of horror fans is legendary, and the genre’s appetite for familiar tropes—crosses, speaking in tongues, shadowy basements—has again made it a lucrative space for movie studios looking to follow consistently repeatable (and profitable) formulas targeted at American horror culture.

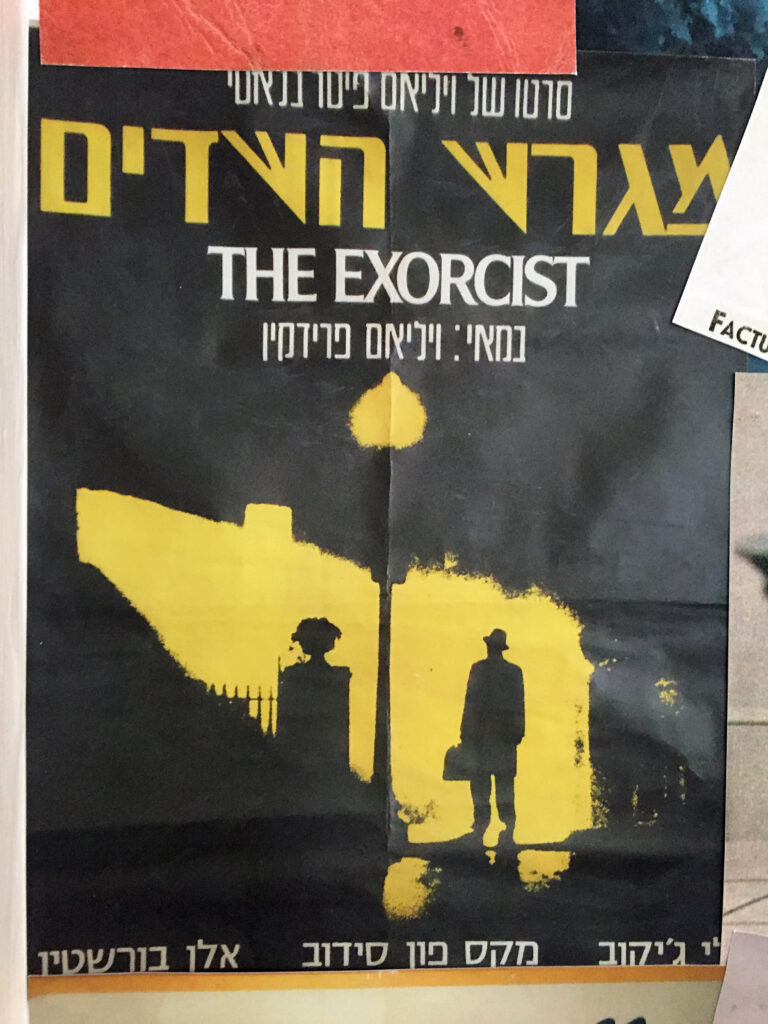

Movie poster for the 50th anniversary re-release of ‘The Exorcist’ – in Hebrew, no less

FLIRTING WITH TRANSCENDENCE

But this market-driven angle also tells us something about a society that is willing to fork over its hard-earned money to indulge in certain kinds of entertainment. The willingness of audiences to return again and again to exorcism films suggests a deeper psychic investment.

Unlike slasher or zombie films, possession narratives gesture toward something beyond death—toward questions of the soul, of absolute rather than relative good and evil, of whether anything exists beyond the visible. Even in commodified form, these stories re-enchant the world. They flirt with transcendence, even as they sell tickets.

To Greymantle, the ongoing revival of exorcism narratives suggests a kind of collective spiritual tic—a cinematic compulsion to return to familiar scripts at a time of massive, society-wide ontological disorientation in the Anglosphere.

Films like The Conjuring or The Exorcism of Emily Rose don’t just scare us with special effects or jump scares; they also flirt with deeper, more existential uncertainties. They pose the question: what if some aspects of the modern, scientific way of understanding the world are just simply wrong? What if evil is not merely a ‘metaphor’?

There is something particularly telling about the timing of this renewed obsession with modern exorcism themes.

In a period marked by rapid technological transformation, social atomization, the weakening of institutional religion, and the rise of online disinformation, the exorcism film functions like a dark mirror held up to the viewer’s own unease. Even those who profess no religious belief are susceptible to the primal fear these films awaken—the idea that one’s mind, body, or loved ones could be seized by something invisible, incomprehensible and malevolent.

A PHENOMENON BUBBLING UP FROM BELOW

Cultural critics and sociologists have begun to take notice.

Some see the trend as symptomatic of the lingering effects of The Exorcist (1973), the huge success of which created a feedback loop: new films borrow from its mythology, audiences interpret personal experiences through that same lens, and filmmakers continue to adapt and reiterate the pattern. Others argue that the persistence of these films reflects a more generalized cultural anxiety—a fear of chaos, collapse, and loss of control in a secular age.

Bloggers and horror fans often complain about cliches in the genre—the Latin chanting, the head spinning, the holy water and the shrouded priest—but still they keep watching. Even when films like The Devil Inside or The Possession of Hannah Grace are critically panned, they often attract loyal audiences and spirited online debate on film criticism sites like Bloody Disgusting.

And there is considerable variation and innovation to be found within the genre

The found-footage format of The Last Exorcism, for example, offers a faux-documentary spin on the genre, playing with audience expectations about authenticity and hoaxes. The Taking of Deborah Logan masquerades as a documentary about Alzheimer’s disease before its plot slowly unfurls into something far more metaphysical and terrifying.

At the Devil’s Door uses possession as a metaphor for female trauma, hidden guilt, and the fragility of modern identity. These films offer new angles on the same fundamental dread: the horror of invasion, loss of physical autonomy, and spiritual confusion.

Levitating Woman – A common cinematic image of possession since the 1970s

The best of these works do more than rehash old tropes. They grapple with the instability of the modern self. What if your thoughts aren’t entirely your own? What if your body betrays you? What if there exist forms of suffering from which the combined powers of reason, therapy, and technology simply cannot save us?

This is where our deeper analysis begins. Because as much as these films function as entertainment, they also serve as a kind of meta-cultural confession. They reveal a society in which roughly half the population no longer believes in Hell – but still fears it. A society that has discarded religious ritual (this is true of most forms of Protestantism as much as secularism) but remains haunted by the possibility that supernatural evil is real, seductive, and loose in the world.

And that is why, no matter how often we try to cast it out, the exorcism film keeps coming back.

PART II: HAUNTED BY BELIEF— THE CULTURAL UNCONSCIOUS OF THE POSSESSION FILM

If the first wave of exorcism films, beginning with The Exorcist in 1973, shocked American audiences with the spectacle of blasphemy and the dramatic power of Catholic ritual, then the recent resurgence of possession cinema operates on a different frequency.

The Latin incantations, the writhing (mostly female) bodies, and the ambient flicker of candles remain—but something fundamental has shifted. We are no longer just watching battles between God and Satan; we are also watching people try to believe – both on the screen and in the cinema seats next to us – that such a battle is even possible.

These films no longer assume a stable worldview in which the sacred and the profane are clearly delineated. Instead, they dramatize a profound loss of existential orientation, a collapse of meaning that reflects the contradictions of life in a post-religious, late-capitalist order.

The demons may be metaphors, but they are also surrogates—stand-ins for the things we no longer know how to name. The same applies to religious symbolism in film.

So, what are we really exorcising?

POSSESSION AS POSTMODERN GUILT

The most revealing trend in recent possession films is the collapse of certainty.

In The Taking of Deborah Logan (2014), what begins as a found-footage documentary about Alzheimer’s devolves into supernatural horror, but it’s never quite clear whether the horror is real or imagined. Likewise, At the Devil’s Door (2014) blurs the lines between mental illness, spiritual vulnerability, and generational trauma. The viewer is left in a liminal space—one foot in the rational world, one foot dangling over a churning abyss of ontological possibility.

This narrative ambiguity is not just a stylistic flourish; it reflects an ambient cultural anxiety—a vague, pervasive sense that something is wrong in our lives, even if we can’t say what it is.

Critics and cultural theorists have long remarked that guilt doesn’t disappear as societies become more secular; guilt simply loses its name – or goes by other names. Human beings have plenty to feel guilty about: lies, betrayals, exploiting other people, envy, hate, murder. As the old saying goes: Man is a Wolf to Man. But if Man is a wolf, then he is a wolf with moral awareness who is amply capable of feeling both guilt and shame.

In the absence of shared religious frameworks, feelings of guilt and shame don’t vanish—they metastasize. They attach themselves to political outrage, performative morality, consumption habits, even mental health discourse.

In that sense, the possession film has become a kind of symbolic processing center for displaced emotions. The demon isn’t Satan. The demon is the return of the repressed.

THE FEMALE BODY AS BATTLEGROUND

It is impossible to ignore that in most of these films, the possessed are overwhelmingly young women. Whether it’s Regan in The Exorcist, Nell in The Last Exorcism, or the tormented title character of Deborah Logan, the genre persistently stages possession as a crisis in—and over—the female body.

This is where the genre’s cultural politics become particularly pointed. The possessed woman is not just a victim of supernatural forces; she is a flashpoint for social anxiety about female agency, sexuality, aging, and autonomy. In many films, possession coincides with puberty, motherhood, or old age—the liminal moments when a woman’s body becomes a site of transformation and, often, societal discomfort.

Some cultural critics of the left argue that these dramatizations reproduce, sanction and codify conservative tropes about women’s dangerous, unruly bodies and are feeding into a dangerous ‘Satanic Panic’ revival. Others see them as coded performances of how culture disciplines female behavior. Either way, the imagery is striking: the female body becomes a canvas for repressed cultural fear, both sexual and spiritual.

As a side note, it is worth mentioning that the subject of the 1949 exorcism upon which the original Exorcist film and its novel are based was not a 13-year-old girl, but a 14-year-old boy known as ‘Robbie Manheim’ (a pseudonym to protect his identity).

As to the relative proportion of purportedly possessed individuals by age and sex, no broadly agreed upon data exists. The well-known Italian exorcist, Fr. Gabriele Amorth, stated his belief that the incidence of possessions by sex was roughly equal in his 1999 memoir, “An Exorcist Tells His Story”.

THE SPIRITUAL CRISIS OF THE MODERN VIEWER

Exorcism narratives once assumed a dualistic cosmos: evil exists, but so does good, and good has the tools—prayer, faith, divine authority—to prevail. But many contemporary entries in the genre depict religious rites as either impotent or corrupted. Priests fail, the church is complicit, and salvation—if it arrives—is fleeting or ambivalent.

This is the terrain of spiritual derealization. The sacred hasn’t disappeared, but it has become unmoored, stripped of institutional coherence and shared cultural understanding and filtered through irony, trauma, or media spectacle. This new, post-modern framing influences much in the recent exorcism movies trend.

In The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005), the titular event is less a sacred battle between good and evil and more a courtroom drama—an epistemological inquest into what counts as truth. The Last Exorcism (2010) plays as a meta-commentary on belief itself, following a disillusioned preacher who performs exorcisms that he knows to be fake—until one of them isn’t.

These films don’t ask: Do demons exist? Instead, they ask: What if we’ve lost the capacity to even recognize what is true? What if we can no longer distinguish the real from the unreal?

Promotional poster for the television program ‘Evil’, circa 2022

MINING AMERICA’S CRISIS OF SHARED REALITY

These questions point to the core tension that gives the exorcism genre its peculiar vitality in the American context: the fact that in the U.S., exorcism-themed stories aren’t just a symbolic or cultural residue from the ‘old culture’ as they are in Europe or other parts of the Anglosphere, but still carry serious ontological weight for a large share (approx. 50%-55%) of the population.

It is from this tension that demonic-themed films and television shows derive their strange double valence: they are both metaphors and direct reports – depending on who’s watching. Because what distinguishes the U.S. from its other, more secular peers in the Anglosphere is this ongoing coexistence of rationalism and religious literalism in the cultural mainstream.

In the U.S., religious believers, including religious literalists, share political and cultural space with equally large numbers of atheists, agnostics and followers of heterodox and non-Christian beliefs. This tension exists at the core of 21st century American social and psychological reality.

The exorcism genre thrives in that space because it doesn’t resolve the contradiction—it dramatizes it.

EVIL: THROUGH THE ONTOLOGICAL LOOKING-GLASS

No work embodies this strange valence better than the television series, Evil (2019-2024), which explicitly toggles between scientific and theological explanations without ever fully privileging one. In that sense, Evil is diagnostic of America’s fractured epistemology. It dramatizes not just possession, but a national inability to agree on what constitutes reality. Evil may also be the most intellectually self-aware exploration of the exorcism genre in recent memory.

Part procedural, part metaphysical thought experiment, the narrative is structured around a trio of investigators—a psychologist, a priest-in-training, and a tech expert—tasked with evaluating supernatural claims for the Catholic Church. The show deliberately blurs the lines between mental illness and possession, hallucination and haunting, algorithmic manipulation and demonic intent to keep the viewer actively engaged and thinking.

What begins as a premise borrowed from The X-Files quickly morphs into something stranger: a meditation on fractured realities. Evil understands that the real horror in 21st-century America isn’t the demon behind the door—it’s the fact that no one can agree on whether the door even exists.

What makes Evil so distinctive, then, isn’t that it takes a position on whether the devil is real. It’s that it dramatizes the impossibility of consensus in a society where shared truth is in decline. The show doesn’t resolve the tension between belief and skepticism—it lives inside it – as Greymantle has argued previously on these pages.

That ambiguity, rendered with narrative intelligence and moral unease, offers not just a mirror to the genre but to the fractured state of American public life itself. Evil doesn’t just exemplify the modern possession story—it helps to explain why we keep telling it.

The show doesn’t try to settle the debate between science and faith, pathology and possession. Instead, it renders the collapse of shared meaning as the scariest phenomenon of all. And in doing so, Evil becomes something rare: not just a reflection of the genre, but a diagnosis of the culture that keeps it alive.

POSSESSION CINEMA AS CULTURAL BAROMETER

If we take the exorcism genre seriously—not as theology, but as cultural expression—then we should best view it as a barometer of collective unease. These films are not about the persistence of orthodox religious belief. Rather, they are about the absence of shared belief and meaning, and what floods into the vacuum left behind.

In an age where institutional religion has retreated from public life, and where spiritual life is increasingly mediated by therapy, memes, and algorithmic “content,” the exorcism film gives shape to long-dormant fears. That the self is not sovereign. That evil is real but unnameable. That our rituals have lost their power. That something is watching, even if we don’t know what.

Possession cinema can’t solve these anxieties. Indeed, it doesn’t even fully acknowledge them. But it embodies them—in bodies that levitate, contort, and speak in ancient tongues, trying to tell us something we no longer quite understand.

CODA: SPEAKING IN TONGUES

The exorcism story endures not only because we suspect our demons aren’t gone, but because—here in America, at least—millions still believe they were never myths to begin with. That’s the uneasy brilliance of the genre: it operates on two frequencies at once. For some, it’s a metaphor. For others, a documentary in disguise.

In a country where reality itself has fractured—into science and revelation, secularism and supernaturalism—exorcism narratives offer something like a shared grammar for describing evil, even if no one agrees on what causes it.

It’s why shows like Evil feel so eerily timely: they don’t necessarily ask us to choose a side. They just sit within the fracture. And in that sense, these stories may be the closest thing we have to a common liturgy. Not because they promise salvation—but because they refuse to let us look away from what haunts us.

The exorcism film endures not only because we (or some of us) still believe in demons, but because we suspect that we still haven’t convincingly explained them away.

It is a strange kind of modern faith. Not in salvation – but in haunting.

Until next time, we remain –

Greymantle