Dear Readers: Hello again. I hope you’ve all been well. My apologies for a quiet month, which I hope to make up for with this post.

Recent events such as the collapse on March 9 of Silicon Valley Bank and the Russian military’s continued failure to take the Ukrainian town of Bakhmut have been leading me to think more broadly about the nature of failure.

What is it to fail? Put simply, failure consists of setting an objective for oneself or for one’s organization, be it the military, a political party, a bank or whatever and then being unable to achieve it.

Failure happens all the time. It’s almost as common, and perhaps more common, than success. The strange thing about failure is that it happens to people and organizations who have long track records of success – sometimes very spectacular success – before they fail spectacularly in the attempt to reach some goal they consider eminently achievable.

Spectacular failures by the very successful have lately become a notable feature of 21st century life.

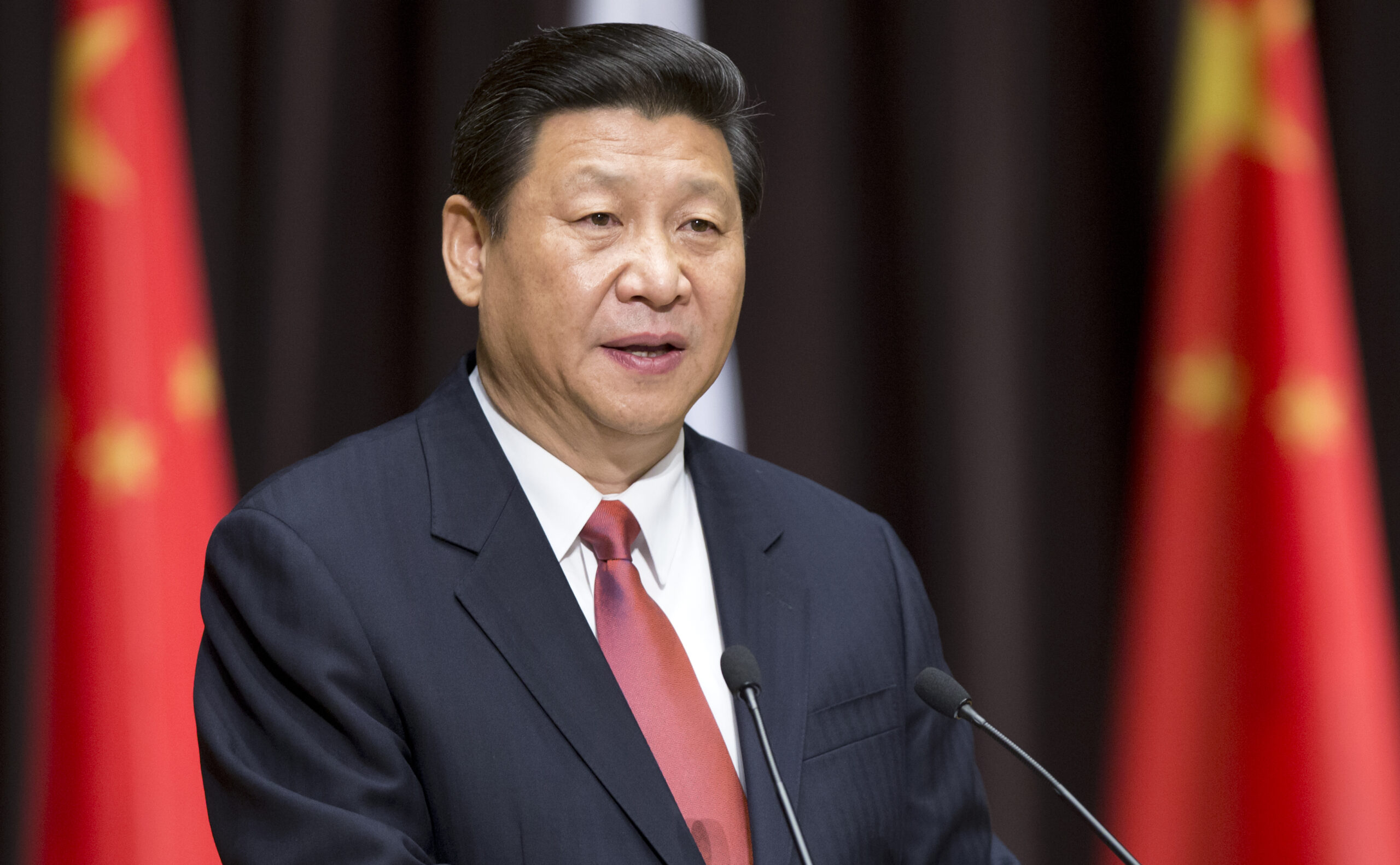

Vladimir Putin was arguably the world’s most successful political leader before the Ukraine debacle of 2022. He has ruled Russia since 2000 and scored many notable domestic and foreign wins against a variety of opponents. Yet now he finds himself caught like a bear in a trap in Ukraine, unable to claim victory or to retreat.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was the 16th largest bank by deposits in the United States before a run by depositors and fire sales of its stock by investors sent it into receivership on March 9. SVB services the wildly successful US technology industry and its associated venture capital firms. Investors believed it was impregnable until days before its failure.

The American conservative movement rose in the 1970s as a fringe movement in the Republican Party. It grew in power until it dominated not only the GOP, but the country. But after having finally taken control of the Supreme Court and overturning the Roe v. Wade decision, the conservative movement appears to be in sudden retreat.

The movement’s annual CPAC conference in late February was poorly attended and largely a one-man show for Donald Trump. The speakers came across as a bunch of cranks and fringe figures. After decades building a mighty power base, why is conservatism suddenly in retreat?

Greymantle believes these failures, these sudden and apparently inexplicable turnarounds in fortune, have a common cause: a failure of the imagination.

BETWEEN OUR DESIRES AND THE WORLD’S

All successful people and organizations create their success through a combination of savvy knowledge of their milieu and an ability to exploit holes in the thinking and adaptability of their opponents and competitors. I define the term “opponents” very broadly here. It could literally mean every other human being.

A successful serial killer keeps getting away with his crimes because he views every other person as a potential witness. It is the paranoid and overactive imagination of the serial killer that keeps him out of jail.

Very successful industry groups, like the technology industry, rose to power and prominence by understanding that modern organizations had become too complex to run by paper methods. A translation of paper data to digital data was essential to run organizations efficiently in the modern age.

The powerful imaginations of men like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates allowed them to see how silicon based computer technology could revolutionize both business and personal life by making computers smaller and faster. Within 20 years of their establishing Apple and Microsoft in the mid 1970s, personal computers were ubiquitous in business, homes and government.

Organizations unable to discern that the personal computer was going to change everything and adapt were flattened. Their failure was dismissing the challenge posed by greater computing power. It was a classic failure of imagination. The leaders of the organizations that failed could not imagine that speed and autonomy would rule the day.

THE TROUBLE WITH LIVING IN THE WORLD ‘AS IT IS’

Vladimir Putin is known to be a savvy man. He rose to power in Russia by becoming a classic ‘organization man’. He mastered the internal workings of the KGB and swiftly rose through its ranks. When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, Putin nimbly aligned himself with the new players in democratic politics while staying in close contact with his former KGB associates.

With the patronage of Russia’s new democratic leaders like Boris Yeltsin and Anatoly Sobchak and clandestine support from KGB elements, Putin was nominated for the Russian Presidency in late 1999, won the March 2020 presidential election, and has been in power ever since.

One of Putin’s apparent strengths is to align his goals and objectives with reality. He is a man who believes in living in ‘the world as it is’. Put simply, Putin is not much of an idealist. In his view, which one must assume has been repeatedly born out in his dealings with other people, human being are motivated mainly by fear, greed, status and a desire for security.

The problem with living in this ‘world as it is’ is that one can become used to the general patterns of human nature and eventually not notice, or at least fail to assign much value to the world’s less dominant features.

What do I mean by ‘less dominant features’? Chiefly the weaker but very real human desires for dignity, love, stable rather than arbitrary-and-ever-changing rules, and a hunger for fairness and honesty in human relations.

Another, less dominant but salient feature of the late modern world is the retreat of individuals from authority and the traditional structures associated with it.

Across much of the world, and certainly outside of the Islamic and Sinic cultures, human beings crave autonomy and choice. They desire dominion over their own lives in ways that pre-modern people and even early modern people in the 18th and 19th centuries simply did not.

The relative success and durability of the Western democracies and the secular, non-traditional societies they have gradually brought into being serves as a continued temptation for people living in less free cultures to emulate this new model.

A TRAP FOR THE WORLDLY-WISE MAN

Although Putin has much abstract data at his fingertips to confirm the reality of the desire for autonomy and dignity, his life experiences and cultural molding lead him to dismiss these desires as something fringe, even deviant. At least when it comes to Russians and other Slavic peoples.

The only way Putin was able to understand the situation in Ukraine prior to 2022 was that a small group of deviant or ‘aberrationist’ politicians had taken control of the government of Ukraine. They did this in spite of, rather than because of, the desires of Ukraine’s popular majority.

Because Putin is a man molded by the organs of the Russian state, he also continues to believe that the CIA was directly responsible for the overthrow of the last Ukrainian president loyal to Moscow in late 2013.

The fact that huge popular demonstrations in Kiev and elsewhere were the main cause of Victor Yanukovich’s fall from power in the winter of 2013-14 is discounted by Putin. He apparently believes with complete certitude that the CIA and other NATO-aligned groups (British and French intelligence, etc.) organized and bankrolled the demonstrations.

This is the trap that a worldly-wide man who deals in raw power, fear and intimidation can fall into. If everything, all the time, is a zero-sum game of power and prestige, then a phenomenon like a groundswell of popular defiance can only be regarded as another tool in the hands of enemies. The populace can never be made up of individuals with their own views.

For Putin, this has become a serious trap indeed. Because Putin can only conceive of people acting as unwitting tools of rival power centers – with some potential for short-lived bursts of defiance, perhaps – he is unable to conceive of a sustained act of popular opposition.

That is what the present government of Ukraine represents, of course. The entire government is more or less a sustained expression of the Ukrainian popular will to crawl out from under Moscow’s thumb.

Therefore, the ferocity of the Ukrainian resistance to Russia’s February 2022 invasion has really taken Putin aback. After 13 months of missile strikes on homes and infrastructure and the death of an estimated 40,000 civilians and 50,000 Ukrainian military, the people of Ukraine continue to defy Putin.

For him, it is all a mystery. He can’t understand why the Ukrainians won’t simply act ‘rationally’ and avoid the horrors of invasion and war by knuckling under to his demands. Why can’t they just see reason? This is Putin’s refrain to his close associates.

TRIMMING THE HEDGES

Next we come to the FTX crypto exchange and its founder, Sam Bankman-Fried, or SBF as he is commonly referred to in the press.

Greymantle has worked in the financial industry for going on 25 years and has seen a lot of crises come and go. I’m thinking of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, Enron in 2002, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the crypto-currency meltdown of 2022, and now the SVB failure.

All of the organizations referenced in the above events were headed by savvy individuals. They lived by ‘the rules of the world’. The problem, I think, is that we often understand the rules of the world through a kind of cognitive shorthand that fails to capture how complicated these so-called ‘rules’ tend to be in actual practice.

To be totally transparent, Greymantle should point out that several of the crises mentioned above involved massive fraud. That was certainly the case with Enron and with Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto operation, FTX, which collapsed in late 2022. The roots of the 2008 Financial Crisis also contained notable elements of fraud related to mortgage-backed securities, but a once in a century real estate bubble was the primary cause.

That being said, in each of the financial collapses referenced above, operators who were otherwise exceptionally savvy got sucked into the whirlpool of bubble-to-bust financial crunches because they started to believe their own hype.

Enron’s ‘smartest guys in the room’ believed their highly leveraged energy trading schemes would never backfire because they had ‘hedged’ away all the associated risks using complex derivative instruments. The problem was that the hedges didn’t work. The revelation that Enron’s top managers had been cooking the books for several years neutralized any protection the derivatives may have given.

NEVER GET HIGH ON YOUR OWN SUPPLY

Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) was an outspoken evangelist for the virtues of crypto-currencies even as he traded a growing number of such currencies on his FTX platform and launched his own crypto-currency. But a single firm cannot simultaneously act as a market’s main exchange, as a store of value, and as the lender of last resort, particularly when a crisis of confidence hits.

A run on the exchange was inevitable when members learned that SBF had withdrawn funds from Alameda Research, his crypto investment fund, in order to meet withdrawal requests from counter-parties trading on FTX.

Four hundred years of bank runs, commodity bubbles and stock market crashes should have taught SBF the financial world’s laws of gravity.

Apparently, the MIT-educated entrepreneur believed his own wild-eyed hype concerning the safety of crypto. When the new market proved infinitely riskier than he had expected, SBF resorted to the theft of his investors assets’ to try and save his sinking crypto ship. A sad end.

Perhaps SBF thought the crypto bubble had more time to run. That he still had ample time – three to five years – to secure his fortune and get out before the crypto bubble burst. SBF’s failure lay in his inability to realize that the life cycle of each new financial instrument and its associated bubble is getting shorter and shorter. The runway before each new crash is shorter than the last one. Not grasping that was his imaginative failure.

TOO BIG TO FAIL, AGAIN

Which brings us to our latest financial collapse – that of SVB. In the case of SVB, systemic fraud does not seem to have been an issue. Neither were the companies and products invested in by the bank valueless. Quite the opposite. SVB’s depositors, creditors and investors included some of Silicon Valley’s top technology firms and brightest names.

SVB was the 16th largest US bank by deposits as of 2022, as has already been mentioned. SVB certainly had been riding the wave of a major technology bubble relentlessly upward.

From management’s point of view, the bank was diversified across the sector. Their funds were invested in software, hardware, AI, cloud computing, cyber security and also crypto. Even if parts of the sector were entering a correction, many market niches appeared insulated.

The failure of SVB’s management team lay in their decision to concentrate the bank’s assets in long-term and ostensibly safe securities that included US Treasuries, municipals and other long-maturity government debt. There are no safer investments than low-coupon, ‘AAA’-rated government paper the bank’s managers must have reasoned. Right?

Wrong.

The problem with long-dated maturity instruments is that their value can fluctuate dramatically when interest rates change. And some of them – municipal bonds in particular – are highly illiquid. This means that they are difficult to sell at short notice. It may take the seller days or weeks to find a buyer. But in the middle of a classic bank run, the seller doesn’t have days to find a buyer. He has hours. And sometimes only minutes.

When the US Federal Reserve commenced a series of rapid short-term interest rate increases in March of 2022, SVB’s portfolio of largely long-dated assets rapidly began losing value. After 15 years of keeping rates artificially low aka ‘financial repression’, the Fed was changing course in an effort to quash the biggest surge of US inflation since 1979.

Not only the speed of the rate hikes, but the size of the hikes – including four back-to-back rate increases of 75 basis points (bps) each – struck the portfolios of fixed income investors like a cyclone. Long-dated US treasuries and munis sagged in value with some losing between 15% and 20% of their par value between March and December of 2022.

When investor confidence in SVB began to sag in early February 2023, the bank was forced to begin selling securities from its asset portfolio to meet the redemption demands of large depositors and investors. But with asset values declining, SVB was forced to sell sizable blocks of securities at a discount, losing nearly $2 billion on $18 billion of asset sales.

As SVB’s losses mounted and became public knowledge, a classic bank run began in the first week of March. Unable to meet depositor requests for withdrawals, SVB fell into receivership and the Fed stepped in to take temporary control of SVB. Fearing a broader banking crisis, the FDIC took the unusual step of guaranteeing all depositor accounts.

Much like the case of Bear Stearns in 2008, SVB had become “too big to fail” as the feds were not willing to risk a broader financial contagion.

ADDICTED TO EASY MONEY

Was Silicon Valley Bank’s failure mainly the result of poor asset allocation? Did it merely amount to sub-par asset management?

It’s been widely reported that SVB’s Chief Risk Officer position was vacant for a year prior to the bank’s collapse. Management had been interviewing candidates for the job, but hadn’t settled on anyone.

The absence of a dedicated Chief Risk Officer in the year prior to the bank run probably accounts for some aspects of SVB’s demise, but it can’t be the whole explanation.

Any CRO hired last summer would still have been faced with fallout from the Fed’s rate hikes on an asset pool composed mainly (57% of the total versus 24% on average for the top 50 US banks) of illiquid long-term debt that was rapidly losing par value.

A CRO could have advised the SVB’s board of directors to start selling, to begin repositioning their portfolio. However, it’s more than likely the board would have rejected such advice, not wanting to take the billions in losses that an aggressive asset repositioning would have entailed.

Greymantle contends that SVB’s imaginative failure began years earlier in the 2010-19 decade when, as already mentioned, the Fed held short-term rates artificially low for a decade after the 2008 Financial Crisis.

For banks and hedge funds, the 2010s decade was the ultimate era of ‘easy money’. Even more so than in the run-up to the 2008 debacle, an accommodative Fed spurred credit creation on an epic scale in a bid to boost growth in a US economy still reeling from the largest spate of bank failures since the Great Depression.

Investment bankers and venture capitalists loved the new credit bubble as it created an environment conducive to large debt financings for an array of speculative projects that included entire new industries (e.g. electric cars, AI, cloud computing and a host of legal gambling operations).

The problem with easy credit is that banks and bankers get addicted to it.

Under an easy credit paradigm, low interest-bearing assets will slowly grow to dominate banks’ asset portfolios. Thousands of junky projects funded at low rates gradually honeycomb the system, waiting to tumble the moment rates begin to rise. Equity markets freak out at every rumor of higher rates. Think back to the ‘Taper Tantrum‘ of 2013 and you’ll get the idea.

THE FALLACY OF NOW

The imaginative failure of the SVB board lay, Greymantle believes, in the unconscious adoption of the belief that the Fed could never raise interest rates above 3% again in their lifetimes.

Because low US inflation had become such an entrenched feature of the US economy, the Fed was under little pressure to raise rates. When it began to do so, finally, in Dec. 2015, it was at a decidedly gradual pace. It took the Fed three years to raise the short-term Fed Funds Rate from 0% to 0.25% up to the 2.25% to 2.50% target reached in Dec. 2018.

What was the SVB board’s take-away from these broad patterns? Greymantle would describe it as ‘the fallacy of now’. Put simply, the fallacy of now arises when people come to believe that a certain set of present conditions are likely to persist indefinitely.

Looking out at an interest rate environment that many of the smartest minds believed was going to persist for decades, the SVB management and board doubled down on long-dated Treasuries and other government investments. In the opinion of many financial experts, these are the safest asset classes in existence: low risk, long-term, low coupon bearing but unlikely to lose par value except under the most unusual circumstances.

It all seemed like a safe bet. Then came the pandemic. A ‘Black Swan Event‘ among black swan events.

A SUDDEN SHIFT IN PARADIGM

In an election year, neither the incumbent president nor a closely divided Congress was going to let citizens bear the financial pain of the pandemic all alone. The result is history. More than $4 trillion of deficit spending by the US Treasury and Congress, flooding state and local governments and citizens’ bank accounts with money the likes of which they had never seen.

A perfect recipe for runaway inflation.

And within 18 months after the fiscal floodgates opened, runaway inflation is exactly what the country had, overturning every recent fiscal and monetary paradigm and returning the US back to the late 1970s in terms of its inflationary expectations and interest rate policy.

Faced with the imminent end of the ‘easy money era’, whole sectors of the tech industry entered into their biggest correction in 20 years – the biggest since the Dot.com Bubble burst in late 2000. And the writing was on the wall for Silicon Valley Bank.

SVB is not alone. The Fed and Treasury are clearly fearful of a wider banking panic unfolding, triggered by recent and coming rate hikes. Hence the raft of emergency measures they took last weekend in the immediate wake of SVB’s collapse. Other major banks have likely been following an asset strategy similar to SVB’s.

It’s going to take two to three years for the asset markets to complete a once in an era repricing, and there are going to be other casualties along the way.

The trick for investors and management teams will be to imagine several possible way forward for interest rates, inflation and financial markets and set a course around them all.

It will take top-notch analysis, clear thinking and imagination.

Part 2 in this series of posts on failure of imagination will follow early next month. In that post, we’ll focus on America’s collapsing conservative movement referenced near the top of this post. We’ll also detail a couple of major failures by police authorities to nab infamous criminals and how those failures involved failures of imagination.

Until then, buckle in for a bumpy ride, both in the markets and in the political sphere.

‘Til next time, I remain —

Greymantle